- Home

- Emily Butler

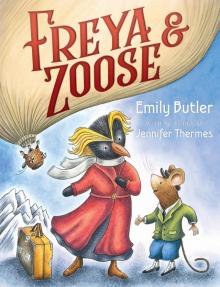

Freya & Zoose

Freya & Zoose Read online

This is a work of fiction. All incidents and dialogue, and all characters with the exception of some well-known historical and public figures, are products of the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Where real-life historical or public figures appear, the situations, incidents, and dialogues concerning those persons are fictional and are not intended to depict actual events or to change the fictional nature of the work. In all other respects, any resemblance to persons living or dead is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2019 by Emily Butler

Cover art and interior illustrations copyright © 2019 by Jennifer Thermes

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Crown Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Crown and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Visit us on the Web! rhcbooks.com

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Butler, Emily, author. | Thermes, Jennifer, illustrator.

Title: Freya & Zoose / Emily Butler ; illustrations by Jennifer Thermes.

Other titles: Freya and Zoose

Description: First edition. | New York : Crown Books for Young Readers, [2019] | Summary: Freya, a penguin, and Zoose, a mouse, become friends while stowaways on Salomon August Andree’s 1897 hot air balloon expedition to the North Pole.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018006937 (print) | LCCN 2018014488 (ebook) | ISBN 978-1-5247-1773-5 (ebook) | ISBN 978-1-5247-1771-1 (hardcover) | ISBN 978-1-5247-1772-8 (glb)

Subjects: | CYAC: Adventure and adventurers—Fiction. | Stowaways—Fiction. | Hot air balloons—Fiction. | Andrée, Salomon August, 1854–1897—Fiction. | Explorers—Fiction. | Penguins—Fiction. | Mice—Fiction. | Arctic regions—Fiction.

Classification: LCC PZ7.1.B89327 (ebook) | LCC PZ7.1.B89327 Fre 2019 (print) | DDC [Fic]—dc23

Ebook ISBN 9781524717735

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v5.4

a

To Sarina, who is held dear by both Freya and Zoose

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Afterword

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

About the Author

There was no question in Freya’s mind that this was her last chance. Either she would find a way onto the balloon, or she would live out the rest of her days on this miserable rock. The men down on the beach nailed the boards of the balloon house together, a shed with no roof. The wind carried parts of their conversation up to Freya’s hideout. From these snippets she knew that she had three nights to prepare for the journey. That was how much time she had to gather the courage to leave.

Men had been here once before, a year ago. They had built the same shed, filled the balloon with gas, and then watched helplessly as the wind knocked it to the ground. They’d left with their tails between their legs. Freya had lacked the gumption to try her luck with that crew, but another year of solitude had almost driven her mad; now she’d do anything to get off the island. And there was something else: she wasn’t a spring chick anymore. If she was going to save herself, it was now or never. No guts, no glory, she thought. Hideous expression.

As the sun began to sink toward the edge of the sea, the men rowed themselves back to their big ship, where they ate and laughed and slept. Freya waddled down to the balloon house and slipped inside. Here she saw the great basket, not yet rigged to the balloon, in the middle of the floor. Would there be room for her and her things? The wicker was densely woven, but she gripped a piece in her beak and tugged. After an hour or so of this, she unraveled a gap large enough to squeeze through.

And what luck! Once inside, she realized that the basket was made of not one but two layers of wicker, with cotton stuffed between them for warmth. Freya plucked some of it out and made a small compartment for herself. “Third-class passage,” she sniffed, “but it will do.”

Then there was much to-ing and fro-ing between the basket and her hideout, as she toted her supplies down to the shed and concealed them in her little berth. She ferried tins of sardines and stale biscuits. There was coffee powder that tasted faintly of dirt, and some mysterious potted meat. Precious packets of Baldwin’s Nervous Pills were squirreled away, as was a suitcase crammed with extra sweaters and a lilac-colored woolen scarf.

Exhausted by this effort, Freya wove the wicker back together and hurried to her cave to rest. On the second night, she was at work again. This time she packed some cakes of chocolate, several items of a personal nature, a suet pudding that was probably five years past its prime, and many strips of bitter green moss that was said to prevent scurvy. Then she went home and crouched at the mouth of her cave to watch the activity on the shore.

Men scurried this way and that. Some measured the speed and direction of the wind. Others oiled ropes and checked the contents of wooden chests. Freya saw the glint of brass nautical instruments. And above it all rose the glorious balloon, shining and rippling in the sun, growing more rotund by the hour as the men pumped it full of hydrogen.

Freya stroked her beloved copy of Hints to Lady Travellers at Home and Abroad one last time to calm her nerves. How difficult the decision to leave the book behind had been. She could not in good conscience add any weight to the basket that wasn’t strictly necessary to her survival—hadn’t she snipped the very fringe off her boots to make them lighter? Anyway, she had long since memorized every word written by Mrs. Davidson, the woman who had governed her adventures.

“My adventure,” Freya corrected herself out loud. There had only been one so far, and look how that had turned out. Misadventure, more like. Tragedy, even!

On the third night, Freya played a last round of checkers for old times’ sake. Then she dropped the black and white pebbles out of the cave and listened to them skitter down the side of the cliff. It had taken her months to collect them, but there was nothing more depressing than playing checkers against oneself, even if one was guaranteed to win every time. She had come to despise the pebbles and the lonely way their clinks echoed off the walls of the cave. Good riddance to bad rubble, indeed!

She filled her canteens with water from the spring, and then there was almost nothing left for her to do except sweep out the cave with beach grass, which she did with scrupulous care. Freya removed Hints to Lady Travellers from its nook in the cave wall and cradled it in her wing. “I fear I’ve become strange,” she admitted to its faded cover. Her final act was to heap some stones over the book, making a sort of tomb. She stood before the mound for a full minute. Then she buttoned her jacket, picked up her canteens, and made her way to the shed on the seashore.

For the third and last time, Freya breached the basket and squeezed herself into the familiar cavity. She did her best to repair the wicker from the inside and waited for the sun to come up. Her heart drummed in her ears. Was she

afraid she might be discovered? Was she anxious to begin the journey? She was many things, but mostly she was determined to leave.

At dawn, she heard the men pull their skiffs up on the gravelly beach. Their jovial voices broke the endless monotony of the surf as their boots pounded the sand, stomping to the shed where the balloon was docked. It billowed up, lofty as a mountain, straining at the ropes that held it to the ground. Freya peered out of the gaps in the wicker basket, which was finally being shackled to the balloon. Oh, the excitement was almost electric! Today was the day, all right.

A tall man, straight as a rod and dressed beautifully in a dark blue jacket, spoke to the small assemblage inside the shed. This was Salomon August Andrée, and he was the captain. His blond mustache shook with authority and dash. Phrases like “we intend to act” and “the weather favors our success” rolled off his tongue and settled over the crowd like a blessing. He lifted his arm to salute the balloon, whose silken panels shimmered back at him obediently.

Next to the captain stood Nils the photographer. For weeks, Freya had watched him carry his black box here and there, making pictures of the expedition. Now his equipment was stored safely inside the basket, but he still observed his companions closely, as if trying to compose their portraits. And Freya knew something the others did not: when nobody was looking, Nils pulled a gold locket from inside his shirt and pressed it to his lips.

The third member of the crew was named Knut, and wasn’t he everyone’s favorite? He was frisky, reminding Freya of the young reindeer she had known in Sweden, though she doubted any one of them could do the trick Knut did on the beach, walking through the surf on his hands.

Captain Andrée’s remarks were interrupted when a man carrying an official-looking clipboard entered the shed and strode through the group with great ceremony. He relayed his information, punctuating it with some taps of a pencil against the clipboard. A squall was blowing in from the south. Perhaps they should wait one more day. The captain’s mustache bristled fiercely as he weighed the man’s words. “No,” he said. “No. We will sail above the clouds. You will see us again in a year—or perhaps two years.”

“I beg you to reconsider. The North Pole will still be there if you leave tomorrow, or the next day, or on Friday!” insisted the man with an urgent tap of his pencil.

“On Friday, the North Pole will fly the flag of Sweden!” said Captain Andrée.

This brought many cheers of “Hurrah!” from the men, and the captain led his crew to the balloon. Freya was elated as they climbed aboard. They stood above her, and she couldn’t see them through the sailcloth that lined the inside of the basket. But she could hear them, and she listened joyfully as the captain gave instructions as to how the shed should be dismantled, and dictated a message to be telegraphed to the newspaper.

Then it truly was time to go. “Cut the ropes!” commanded Captain Andrée. This was done, and Freya felt the unnatural sensation of rising off the ground. Her wings weren’t engineered to lift her body from the earth, and she accepted that limitation of her species. Most penguins of good breeding felt as she did, that grandiose notions of flying were in poor taste. Still, a part of her had always wondered what it would be like to soar through the air. Now she was about to find out.

Peering through the outer basket, she saw the caps on the men’s heads sink beneath her. Then the balloon rose above the walls of the shed, and she could see the cliff and bits of gray sky and some falling snow. The basket swung back and forth as if rocked by an invisible hand. I’m as safe as a baby in a cradle! thought Freya, nestling into the cotton wadding of her dim cocoon. Ah, how lovely. Flying is really the only way to travel!

Her stomach lurched as the balloon soared higher, but this was eclipsed by a wave of good cheer that swelled into something almost ecstatic as the distance between Freya and the island lengthened. She might just as well have been trapped underneath that pile of stones as on top! They had crushed her a little more each day. At the end, right before the men had come back, she sensed that maybe she had become a stone herself, hardly able to move or feel. But now her nightmare was over. She felt nearly weightless, and she relaxed as the misery of the past year drained away. It was replaced by a warm delirium. Freya eased herself against the cotton, stretching her legs out as far as they could go.

Then something pushed back. “Watch it, lady!” came a squeak from the darkness. “You ain’t the only oyster in the stew!”

Freya’s rapture shriveled up like a raisin. “Kindly identify yourself!” she demanded, rattled and angry at the assault on her brief happiness.

“All right, all right,” the voice answered. “No need to get your feathers in a bunch. The name’s Zoose.”

“What are you doing in my cabin?” asked Freya. She twisted around and looked behind her, trying to make out the intruder.

“Your cabin? You’ve got to be joking. I’ve been living in this basket ever since they built it.”

Gradually the voice acquired a shape, and Freya was able to see a furry little face with a pointy nose and two eyes that glittered brazenly. Zoose was a mouse. Freya was neutral on the subject of mice, having never had much to do with them. But she doubted that they made desirable traveling companions. One did not hear tales of illustrious mice on grand adventures. And this one, small and shifty as he was, looked like a rogue.

“You should have made your presence known to me at once,” she said.

“Oh, yeah? Why’s that?” asked the mouse. “Is it a rule?”

“No,” said Freya. “It’s just polite.”

The balloon took a sudden plunge through the air, and both voyagers clung to the basket walls instinctively, Freya with her beak and Zoose with his paws. They listened to the commotion above them. Captain Andrée shouted to Nils and Knut to toss various things overboard, and as they carried out his orders, the basket swung and bobbed fiercely.

“What’s going on?” Freya asked. “Why are we bouncing around like this?”

“Haven’t the foggiest idea,” said the mouse.

“But you said you’ve lived in here from the beginning.”

“And so I have. But this is the first time the basket’s ever been aloft. I don’t know any more about aeronautics than your average earthworm. Or penguin.”

The nerve of him! thought Freya. Was he insulting her intelligence? Or insinuating that she was average? The balloon steadied itself and resumed its progress through the sky. She looked once again through the wicker and tried to enjoy the crisp outline of the island as it receded into the distance. The water was etched with whitecaps that formed regular and reassuring patterns. But Freya was unsettled. She decided to take control of the situation by introducing herself.

“My name is Freya,” she said, sounding more imperious than she had intended. “I’m from Sweden. This is my second voyage, so I am not entirely without travel experience.”

“I’ve lost count of my ‘voyages,’ ” stated Zoose with something like a smirk. “Ran out of fingers and toes.”

Freya ignored this possible challenge. “Where do you come from?” she asked. It was courteous to adopt an attitude of interest.

“London,” he said.

“You’re a long way from home, aren’t you?” she said.

“Not really,” said Zoose.

Contradicting people seemed to come very easily to this mouse, a quality Freya found most disagreeable. She resolved not to ask him any more personal questions, but Zoose continued speaking. “Home is wherever I kick off my boots. I haven’t seen the family in years.”

“How they must miss you,” said Freya drily.

“Doubt it. My mother had a hundred and eighty-one children by the time I came along. We slept in a sock and had to take turns.”

Was there any way to terminate this conversation? “That sounds dreadful,” said Freya.

“On the contrary. Ma did the be

st she could. Gave me a kiss and pushed me out the door when I was two years old—best thing that could have happened to me. Anyway, who needs family? If you’ve seen one mouse, you’ve seen them all.”

Freya’s attempt to mask her horrified expression made him laugh. “I’m joking, of course! Mice are as different as snowflakes. Except for the babies—our own mothers can’t tell us apart. We all look like miniature sausages. You could stick toothpicks in us and serve us as appetizers. Nobody would know the difference.”

This was beyond appalling. Freya began to contemplate her luck. Where traveling was concerned, she seemed to have very little. It was entirely possible that she was stuck with this mouse for the rest of the voyage, unless he accidentally dropped through a hole in the bottom of the basket, which was unlikely. Not that she wished him any harm, but to find oneself in close quarters with someone so vulgar was hard. All things being equal, it struck her as grossly unfair.

“May I ask you,” she said, “how you came to join this expedition?”

“What do you mean?” asked the mouse.

“I mean that we may be penned in here for some time. It would put our minds at ease if we communicated our intentions. I’d like to know what you’re doing in a balloon that is sailing for the North Pole,” said Freya. “Oh, and what your plans are, once we get there.”

Zoose leaned toward Freya, who retreated an inch or two. “Not much to tell. I spent a few years bumming around Europe until I wound up in Sweden, which was the end of the line, more or less. I said to myself, ‘This is decent enough. Why don’t I settle down right here?’ And I found me an empty room behind a cabinet in a woodworker’s shop in Stockholm. Do you know Henriksson’s, down on Kåkbrinken Street? Well, one day a fellow with a fine mustache comes in, the one flying this balloon—”

Freya & Zoose

Freya & Zoose